Chai’s Secret Agent

A Scottish botanist in disguise, a wild bush in Assam, and the long road from smuggled leaves to roadside chai.

Here’s this month’s story from the same series, and big thanks to Krish Ashok for his brilliant video “From Opium to Chai: How Britain Stole Tea & Enslaved Millions.” His research and humour inspired this retelling.

A couple of hundred years ago, tea wasn’t part of everyday life in India.

The British, though, were completely hooked on it.

The problem was that all of it came from China, and China wasn’t interested in British goods.

They wanted silver.

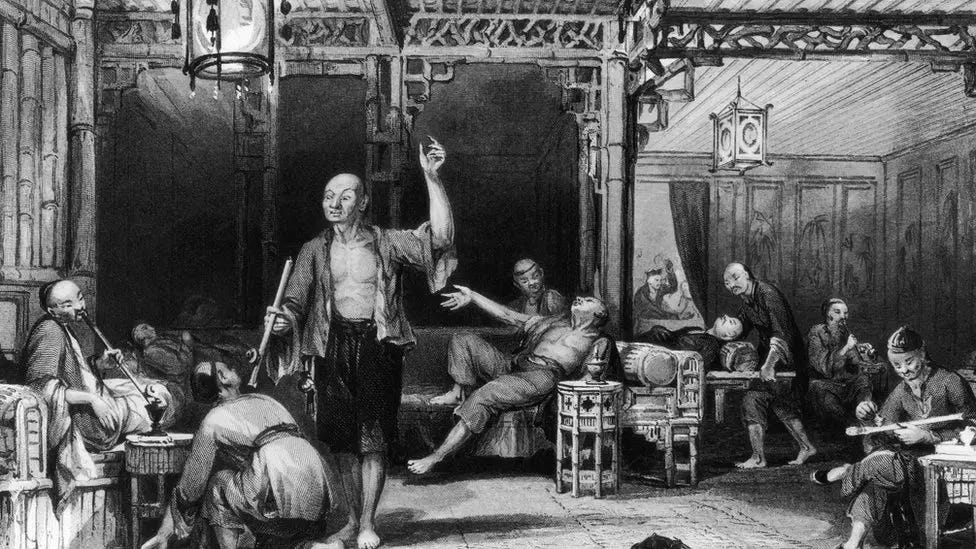

To fix that, the East India Company came up with a trade loop: sell opium grown in India to China, use the profits to buy Chinese tea, and then tax that tea back in Britain.

It worked for a while, until Chinese rulers tried to ban opium. That led to the Opium Wars, which were really about keeping tea supplies flowing.

The British realised war wasn’t a long-term solution. They needed to grow tea themselves, and that meant getting hold of the plants and the know-how from China.

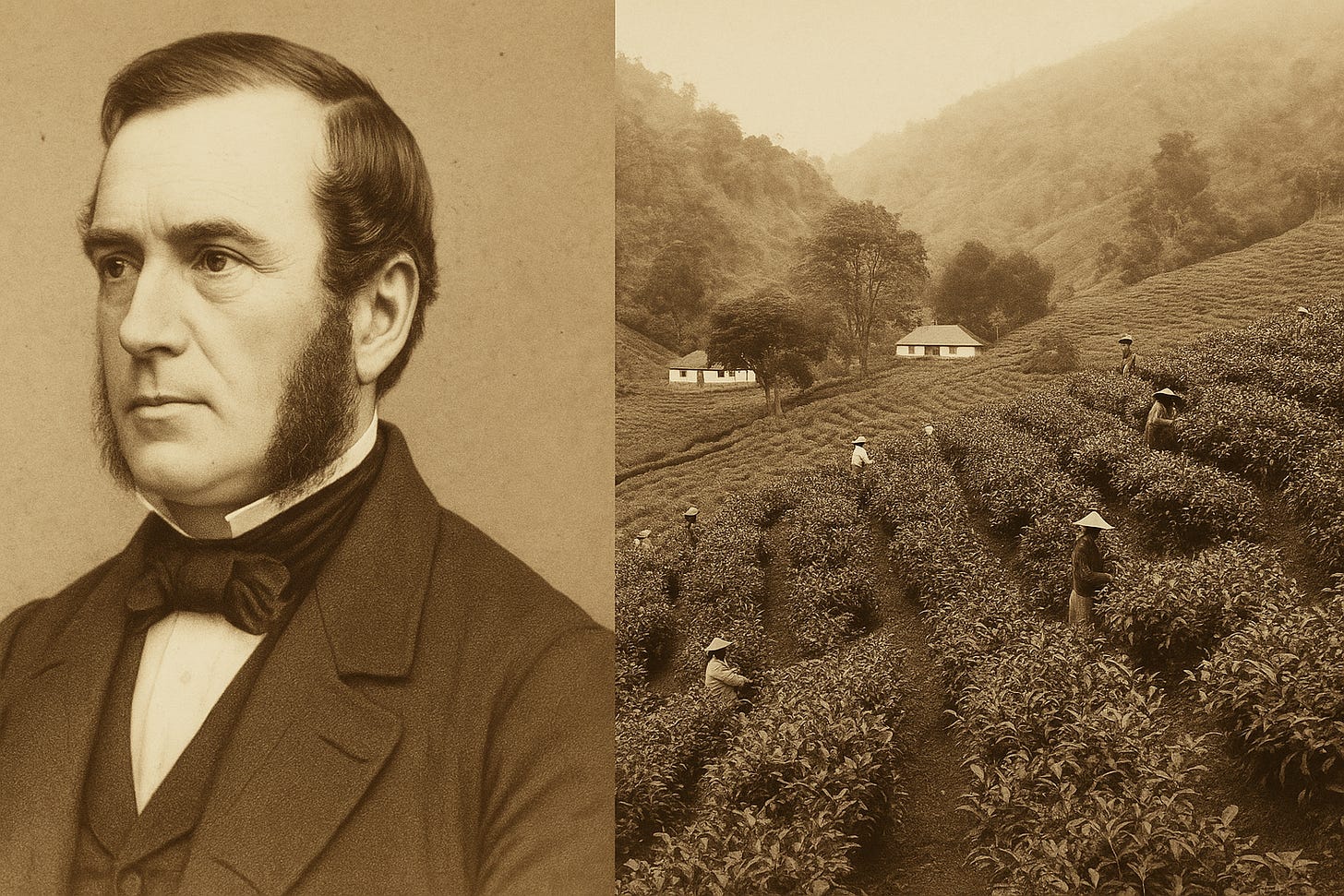

Enter Robert Fortune, a Scottish botanist with an unusual assignment.

In 1848, he was asked to travel into China’s tea-growing regions, where foreigners weren’t allowed, and bring back plants, seeds, and everything he could learn about how tea was grown and processed.

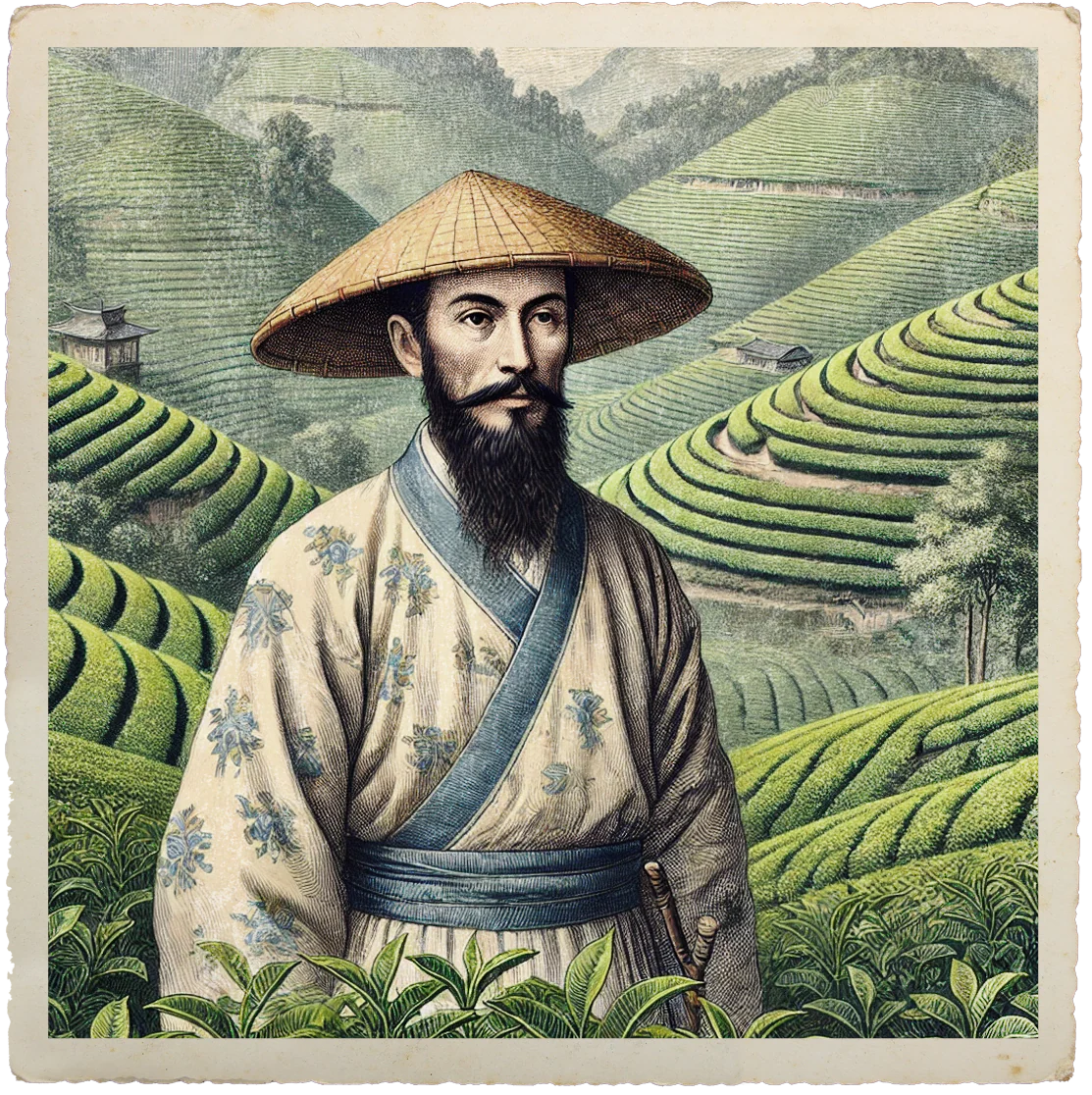

He disguised himself as a Chinese merchant -shaved his forehead, wore a fake ponytail, and put on local clothes and set off into the mountains.

Along the way, he collected thousands of seeds and plants, packed them into glass boxes called Wardian cases so they’d survive the sea voyage, and even persuaded a few skilled tea workers to teach British planters how to handle the leaves.

While Fortune was carrying out his mission, another Scotsman, Robert Bruce, had already discovered tea plants growing wild in Assam, where the Singpho tribes had been using them for generations.

Samples were sent to Calcutta, and botanists confirmed it was a different variety of tea, perfectly suited to Assam’s hot, wet climate.

Together, Fortune’s Chinese seedlings and Bruce’s Assam bushes gave the British everything they needed. Tea estates soon spread through Assam, Darjeeling, and later Ceylon, and tea auctions in London couldn’t get enough.

Behind this success was a harsher story.

Plantations needed workers, and local communities weren’t willing to sign up for backbreaking labour in remote estates.

Recruiters travelled through Bengal, Bihar, Odisha, and Chota Nagpur, often luring or coercing people to move.

The journey was hard, the work exhausting, and many families stayed tied to the plantations for generations. Their descendants are still known in Assam as the tea garden communities.

Even after all this, most Indians still weren’t drinking tea.

It remained an export for British cups and saucers.

To change that, planters launched a huge marketing campaign. They offered free cups at fairs and railway stations, introduced tea breaks in factories, and sent all-women teams door to door to show people how to brew it.

Vendors added milk, sugar, and spices to stretch the expensive leaves, and masala chai was born.

The British weren’t thrilled with the extra ingredients, but people loved it.

After Independence, Indian companies took tea and gave it a new meaning. It became a symbol of hospitality and togetherness. New methods like CTC made it strong and affordable, perfect for roadside stalls, trains, and offices.

Ads in the ’70s and ’80s put chai into pop culture, and today it’s part of daily life everywhere.

The next time you sit down with a cup of chai, remember where it started: Chinese tea leaves, Indian opium, a Scottish spy in disguise, and millions of workers and traders who turned a colonial plan into something deeply Indian.

That’s it for this week.

Manoj

"1 Idea" delivers interesting insights every week straight to your inbox. If this edition resonated with you, how about sharing it with a friend?

And if you're just diving into my world for the first time, why not hit that subscribe button?